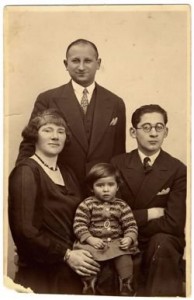

I was born in Berlin, Germany, of Polish Jewish parents in 1928. In 1933, my brother, Hermann, who was fourteen years my senior, saw the threat Hitler posed to Germany’s Jews and urged my parents to leave Germany. My father, who had lived in Germany for over twenty years and was the prosperous owner of a men’s clothing store, scoffed at this suggestion. He was sure that Hitler and his Nazi followers would soon blow over.

I was born in Berlin, Germany, of Polish Jewish parents in 1928. In 1933, my brother, Hermann, who was fourteen years my senior, saw the threat Hitler posed to Germany’s Jews and urged my parents to leave Germany. My father, who had lived in Germany for over twenty years and was the prosperous owner of a men’s clothing store, scoffed at this suggestion. He was sure that Hitler and his Nazi followers would soon blow over.

My brother decided to leave on his own, and, in May 1933, he moved to Antwerp, Belgium. Shortly thereafter, my father changed his mind about leaving Germany, met with a group of Nazis, agreed to give them our business for a fraction of its cost, and they gave us permission to leave.

In July 1933, my parents and I moved to Antwerp. There followed months during which my father and brother tried to find a way to make a living in Antwerp and other European cities, but nothing worked out. My brother made countless applications for visas to permit our family to remain in Belgium; all were denied. Then, my father read that ships were departing for the U.S., and my parents decided we would get on one of these ships. Since my parents had been born in Poland, we were able to get visas for the U.S. on our Polish passports. We left Antwerp on the Red Star Line’s S.S. Westernland in April 1933, arriving in New York City on May 1, 1934.

After we had left Antwerp, the police came to our apartment to serve us with deportation papers; they planned to deport us to Poland, where my parents hadn’t lived in twenty years. Had our visas to remain in Belgium been granted or had we been deported to Poland, we would, in all likelihood, have been killed during the Holocaust.

On arriving in New York City, my family rented an apartment in the Bronx and my father went into the men’s clothing business.

After a summer 1935 vacation in the Catskill Mountains of New York State, my father decided that we would be moving to a village in the Catskills, where he planned to go into the resort business, a business in which he had no experience.

In 1936, we moved to the village of Woodridge, New York, where my parents rented and ran a rooming house for five years. In 1941, my parents bought fifty acres of land in the nearby, larger town of Monticello, where they built a twenty-five-bungalow colony.

I graduated from high school in Monticello as valedictorian of my class and went on to Cornell University, from which I graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, in 1950.

I graduated from high school in Monticello as valedictorian of my class and went on to Cornell University, from which I graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, in 1950.

By that time, my brother was married and living in Long Beach, New York; my parents had sold the bungalow colony, retired and moved to Long Beach, too; and I moved there to live with my parents.

I thought the world would be beating a path to my door. But no such thing happened. I couldn’t get a job until I went to business school and learned shorthand. (I’d already taken typing in high school.) I finished my shorthand studies on a Friday and the following Monday I had a job as a secretary at Fawcett Publications.

By 1954, I felt I was getting nowhere fast, and decided to apply for law school at the University of Miami, FL (since my family and I often spent winters in Miami Beach). My goal was to practice law in a private law firm, something I never thereafter did.

In my final year of law school, recruiters from the U.S. Department of Justice came to the school, and I was accepted for their program for Honor Law Graduates.

After graduation from law school, first in my class, I moved to Washington, D.C., intending to stay with the Justice Department for a few months before moving on to my goal: private practice. That was the start of a twenty-three-year career with a number of federal agencies. I subsequently worked for the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), and the Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD).

Through much of my career, I was looking for another job. From the age of ten, I had felt there was a purpose to my life, a mission I had to accomplish, and that I was not free as other girls and women were simply to marry, raise a family, and pursue happiness. This feeling arose from three factors in my life: I had been born only because my mother’s favored abortionist was out of Berlin, my immediate family and I had escaped the Holocaust, and I was bright. I concluded that I had been saved to make a contribution to the world. But I had no idea what it was to be.

In 1963, as a volunteer with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), I testified before the House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor in favor of the Equal Pay Bill, which was subsequently passed. I assumed that was my first and last effort on behalf of women’s rights–but I was wrong.

In October 1965, three months after it had commenced operations, I joined the EEOC as the first woman lawyer in its Office of the General Counsel–and found the role I was meant to play. The EEOC was charged with enforcement of a new law, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. At that time (it was later expanded to cover discrimination based on mental or physical disabilities), Title VII prohibited discrimination by covered employers, employment agencies, and labor unions based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.

During its first year or so, by and large, the EEOC did not enforce the gender discrimination prohibitions of the Act. Most of the commissioners and staff had come to the agency to fight discrimination against African Americans and did not want the Commission’s time and resources devoted to gender discrimination. Furthermore, the gender discrimination provisions raised more difficult questions of interpretation than did the other prohibitions of the Act.

The Commission’s failure to implement the gender discrimination prohibitions of the Act caused me a great deal of grief and frustration. When Betty Friedan came to the Office of the General Counsel to interview the General Counsel and his deputy for a book she planned to write, I shared this frustration with her. I told her that what this country needed was an organization to fight for women like the NAACP fought for its constituency.

In June and October 1966, forty-nine men and women, of whom I was one, formed the National Organization for Women (NOW).

In June and October 1966, forty-nine men and women, of whom I was one, formed the National Organization for Women (NOW).

Thereafter, I became involved in an underground activity. I took to meeting privately at night in the Southwest Washington, D.C., apartment of Mary Eastwood, a Justice Department attorney and a co-founder of NOW, with her and two other government lawyers, Phineas Indritz and Caruthers Berger. At those meetings, I discussed the inaction of the Commission that I had witnessed during that day or week with regard to women’s rights, and then we drafted letters from NOW to the Commission demanding that action be taken in those areas. To my amazement, no one at the Commission ever questioned how NOW had become privy to the Commission’s deliberations.

As a result of pressure by NOW, the EEOC began to take seriously its mandate to eliminate gender discrimination in employment. It conducted hearings and began to issue interpretations and decisions implementing women’s rights. I drafted one of the Commission’s earliest Digests of Legal Interpretations, its first Guidelines on Pregnancy and Childbirth, and the EEOC’s first decision finding that airlines violated Title VII when they grounded or terminated stewardesses on marriage or reaching the age of thirty-two or thirty-five.

I also became a founder of WEAL (Women’s Equity Action League) and FEW (Federally Employed Women) and a charter member of VFA (Veteran Feminists of America).

While I was at the EEOC, when I was forty-two years old, I married, and when I was 43½, I gave birth to my daughter. Subsequently, I divorced and raised my daughter as a single mother.

I left the Commission in 1973 and in the ensuing years became the highest-paid woman employee at the headquarters of two leading corporations: GTE Service Corporation in Stamford, Connecticut, and TRW Inc. in Cleveland, Ohio.

In 1990, I learned I had breast cancer. I had a mastectomy and simultaneous silicone breast implant. Thereafter, I went on the board of the American Cancer Society (ACS) for the District of Columbia, traveled to Israel and China to look into the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in those countries, and reported on my findings to ACS and in speeches.

In 2005, I discovered that my breast implant had ruptured; I had it removed and replaced with a saline breast implant. Subsequently, I wrote an article on breast implant ruptures and leaks to let the millions of women with implants know that implants have limited life spans.

In 1996, at a ceremony honoring the founders of NOW, Betty Friedan presented me with the VFA Medal of Honor. I was honored by VFA again at a June 2008 program at the Harvard Club in NYC as one of thirty-six feminist lawyers who made significant contributions to women’s rights in the 1963-1975 time period.

In 2000, I was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame and was included in the National Gallery of Prominent Refugees established by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. I was also one of seventy-four women included by the Jewish Women’s Archive in an online exhibit of Jewish American women who contributed to women’s rights. (jwa.org/feminism).

I have lectured and written extensively in this country and abroad on women’s rights. My testimony was presented to a Select Committee of the House of Lords when England was considering the passage of legislation prohibiting gender discrimination in employment, which legislation was subsequently passed, and I was a consultant to the Women’s Department and the Department of Labour for the Province of Ontario when Ontario was considering the passage of such legislation, which legislation was also subsequently passed.

I have traveled as an “American specialist” on women’s rights for the then-US Information Agency (USIA) to France, Germany, Spain, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia, giving talks and meeting with women and representatives of labor, industry, academia, and the professions.

In 1993, I retired and for over a year I went through a difficult period wondering what to do with the rest of my life. Eventually, I wrote my memoir, Eat First–You Don’t Know What They’ll Give You, The Adventures of an Immigrant Family and Their Feminist Daughter, and moved to Sarasota, FL.

In 1993, I retired and for over a year I went through a difficult period wondering what to do with the rest of my life. Eventually, I wrote my memoir, Eat First–You Don’t Know What They’ll Give You, The Adventures of an Immigrant Family and Their Feminist Daughter, and moved to Sarasota, FL.

I embarked on new careers as a writer, public speaker, and community and feminist activist. Currently, I am co-president of the Sarasota chapter of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, a member of the local chapter of NOW, a member of the program committee of the Congregation for Humanistic Judaism, and the first and only honorary member of the Sarasota chapter of the Florida Association of Women Lawyers.

This June, at its annual national conference in Tampa, FL, NOW will present me with an award for being a co-founder and for my work at the EEOC.

I returned to Germany once since I left in 1933, as a speaker on women’s rights for USIA in 1978. I plan to go again for a week this September, at the invitation of the German government.

After that, I plan to spend several days in Antwerp as the guest of the staff of the Red Star Line Museum. That museum, dedicated to the Red Star Line and due to open in the spring of 2013, will have a permanent exhibit about me and my family. This will be my first time back in Antwerp since I left in 1934.

Find me at: http://www.erraticimpact.com/fuentes

2 comments

Sonia Pressman Fuentes

Thanks so much, Gretchen. It’s been a pleasure working with you.

Best,

Sonia

gretchen

Sonia – what a wonderful legacy. You’ve taken what life handed you and helped change the lives of many women for the better. I love your passion and your fight. You never give up. Thank you so much for sharing your story with us!